Water. It’s one of the most basic elements of life, so much so that most of us don’t think much about it on a daily basis. We turn on our taps at home and clean, safe water comes pouring out on command. We carry bottles of drinking water, wash our clothes and shampoo our hair and rarely stop to think what an essential gift of life it is and what a miracle it is that it comes to us so readily.

By Shelly Seale, Photos by Cody Hamilton

Sarah Evans was once one of those people, never thinking twice about where water was coming from, getting scolded by her father as a kid for filling the bathtub up to the maximum. But in recent years, that has all changed. Today, Evans knows firsthand the value of water—and just how deeply the absence of it affects lives.

Born in Australia, Evans moved at the age of 5 to the small, rural town of Crockett in East Texas.

“I had a hard time fitting in at first,” she recalls.

Eventually, her “foreignness” faded and she began making friends. After high school, Evans came to Austin to attend the University of Texas, where she changed her major several times but eventually graduated with a degree in communications in speech in 1998.

Eventually, her “foreignness” faded and she began making friends. After high school, Evans came to Austin to attend the University of Texas, where she changed her major several times but eventually graduated with a degree in communications in speech in 1998.

From there, it was on to law school at Southern Methodist University on a scholarship. There, she was first introduced to global water issues while clerking for the Environmental Protection Agency. After graduation, Evans got a job providing in-house legal services for a finance company in Dallas.

“I was learning a lot about the field, but it was an intense job. I was working all the time. It was just a world that I didn’t feel I belonged in,” she says.

She came back to Austin and joined a law firm, but was still disenchanted with the field in general. Evans moved to her father’s general contractor company instead, providing legal work, as well as bringing his business in to the digital age. In short, she was a young woman still trying to figure out where she fit in this world.

The answer came in the form of a friend who was trying to raise money to help her father in Kenya because his domestic animals were dying.

“I started asking more questions about the problem, and I realized that what they really needed was clean water,” Evans says. The underlying issue was the fact that the livestock were dying from drinking unclean water; avoiding fixing that would just be a band-aid solution. “I was very naive, but I really wanted to help. The more I read about the issue, the more I realized there was such an incredible need there. I said, what we need to do is to build a water well.”

Evans had no idea just what that would entail, but she was about to find out.

She started raising money for the cause, which she dubbed Well Aware, talking about it to anyone who would listen.

“I was learning more about the cause, and getting a little obsessed with figuring out how to help,” Evans says. “It was deflating and illuminating at the same time when I realized how much I didn’t know. It was like a world opened up to me.”

Sitting on her living room floor with friends, trying to brainstorm ways to make this happen, the idea of a shower strike came up.

Sitting on her living room floor with friends, trying to brainstorm ways to make this happen, the idea of a shower strike came up.

“I worked from home,” Evans explains, “and my friend said, ‘Sarah, you never shower anyway. Why don’t you go on shower strike to raise money?’ It was kind of a joke, but then we all looked at each other and thought, maybe that would work!”

Each of them, and whomever they could recruit, would vow not to shower until they had reached $1,000 each in donations for the project. It seemed like a way to equate the first world of plentiful water for all things, to the life-and-death water situation in Kenya.

“For the people we are helping, a clean drink of water is a luxury,” Evans says. “A shower is unheard of. It’s the least we can do to skip our showers for a week so that others can survive and thrive.”

The group had no plan if it would work, but as Evans says, it turns out the idea was pretty catchy. That first Shower Strike, in 2009, involved 15 strikers and raised $25,000. It was enough to send Evans to Kenya in January 2010 to drill the first well.

It was still her pet project, done on the sidelines while she continued to perform her other work.

“I didn’t know it would become something I would devote my life to,” Evans says. But that first trip to Kenya changed everything. “When I was on the ground and met the people, and saw what incredible impact and transformation it was for these people to go from having to drink contaminated, dirty water every day—and walking kilometers to get it—to having plentiful clean water come out of a faucet, getting to witness that and be a part of it transformed me as well.”

Evans adds that she felt a lot of pain when she was in Kenya that first time.

“It’s hard to be a part of what that reality is for them,” she says. “But it’s what changed me. That’s when I realized this was something I would do forever, that it would be my life’s work even though I didn’t know exactly what that would look like.”

A second Shower Strike organized in the summer of 2010 raised a little more than $30,000 to build a second well in Kenya that August. Evans admits that in a lot of ways, she was fortunate with the success and relative ease of putting in those first two wells.

“After the second trip, it was opening my eyes to everything. This work we wanted to do, there were a lot of problems with it,” she admits. “We had successfully drilled the first two wells that had become the foundation for our organization, but we got lucky, honestly. In order to do this work responsibly, I realized it was going to take a lot more thought and experience with the communities, as well as a focus on environmental and technical factors.”

She was learning a lot of hard truths about the issue, such as the fact that 60 percent of existing water wells in Africa don’t work.

“Everywhere you look, there are broken wells,” Evans says. “There’s a lot to consider for a project that’s sustainable, for a well that will last more than a year.”

Not only had she moved to doing the Well Aware work full time, Evans also encountered a lot of personal challenges as the work consumed her, personally and financially. She gave up a relationship, and her parents bought her house and took over the mortgage she could no longer afford. She also sold her car, along with many personal belongings, and lived off savings for a while. She reached out to friends, who helped her keep going by donating clothes and other things. Eventually, Evans had to move in with her parents in order to stay afloat. It was about this time that she also learned she was going to become a single mother.

“2010 is when my life turned upside down,” she says.

But while the problems were difficult, they were also liberating in a way.

“While I was giving up those things, I was also learning how much I didn’t need them. I mean, I was working in a place like rural Kenya, where the people have nothing,” Evans says. “I’m so grateful for that enlightenment now, that I got to go through that process of shedding things. It helped me to stay in a place of gratitude.”

Slowly, the sacrifices began to pay off. Well Aware started building technical teams of engineers and hydrogeologists, as well as strengthening the board of directors.

“I’m really excited that there’s a heightened awareness of water issues now, but I worry that it’s a superficial awareness,” she says. “The next step now is to focus on the process for the long term. We’re always trying to figure out how we can have better impact.”

Evans and her team knew they now had a good model for long-term sustainability, but at the same time, they were looking at all the water well projects in Kenya that had failed. They started looking for existing wells and initiatives that were good models for rehabilitation, partnering with them to not only fix the broken wells, recycle the pumps and the previous resources, but also to apply their model of sustainability and success for the long term.

Evans and her team knew they now had a good model for long-term sustainability, but at the same time, they were looking at all the water well projects in Kenya that had failed. They started looking for existing wells and initiatives that were good models for rehabilitation, partnering with them to not only fix the broken wells, recycle the pumps and the previous resources, but also to apply their model of sustainability and success for the long term.

“You wouldn’t believe the amount of infrastructure that’s just sitting on the ground in Kenya because someone put in a pump that was the wrong size, or they didn’t set up a local water committee so there was no one afterwards to maintain the well,” she says.

Well Aware’s goal is to identify 10 existing projects to partner with for 2014.

“We’re launching an initiative that will approach water charity in a completely different way,” Evans says. “I’m very excited about it because it breaks my heart to see all those wasted resources.”

Bringing the community together as part of the project is also a vital part of the mission.

“We really do want people to know how important the infrastructure is, and the partnership with the communities,” she says.

Evans felt an incredible connection to the people in Kenya, and, as a new mother, especially with the women. She also discovered that by talking with the women without men around, she got a whole new perspective and information she wouldn’t have otherwise.

“I really did understand for the first time what you will sacrifice for your kids. And how devastating it would be to not have clean water to give your children,” Evans says. “It was even more personal to me. So on a whole new level, this really felt like my path.”

That personal connection and partnership model really informs Well Aware’s philosophy about its nonprofit work. The model is not one of bringing charity to poor communities, but rather one of assisting the communities in their own success.

“They are really organized and prepared, and they know better than we do what they need,” Evans says. “It’s not an unsolvable problem; the communities have potential, and their own solutions for success if given a few resources. We’re not saviors. They just need a kick-start, and we get to help.”

Well Aware is one of the most efficient water charities, being able to provide water to a community for a decade for only $20. The organization has completed 15 water projects in just three and a half years, delivering clean water to more than 35,000 people, and is on track to more than double its impact in 2014. One hundred percent of the group’s donor dollars goes to water infrastructure.

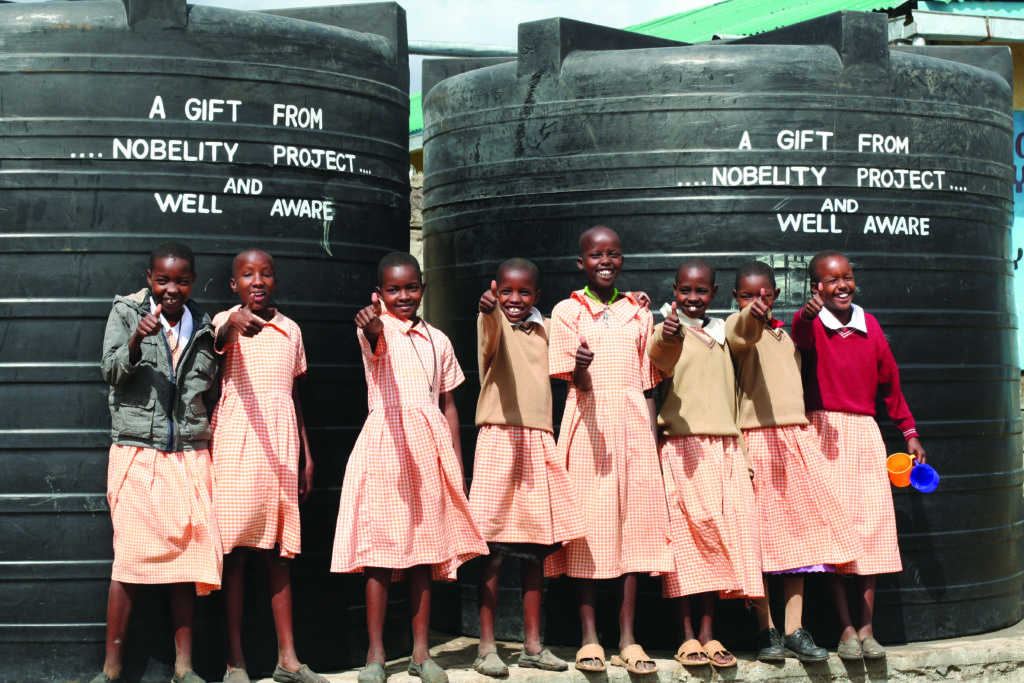

The organization has also partnered with several other Austin organizations that work in Kenya, including CTC International and the Nobelity Project.

“It’s rare to find partners who value collaboration the way Sarah and the Well Aware team does,” says Zane Wilemon of CTC. “I find that extremely encouraging when faced with the challenges we see in Kenya.”

Nobelity has utilized Well Aware as its water-implementation partner for its school locations in Kenya, resulting in happier and healthier students.

“Sarah is as highly committed to bringing a source of clean water to communities as anyone we have ever seen working in the field,” says Christy Pipkin, executive director of Nobelity. “Clear standards, fast action, good research and follow-through make them a high-impact organization and quality partner.”

Evans attributes much of her nonprofit’s success to its approach of “you tell us,” rather than “we tell you.” She is also proud of the extreme leanness of the organization, as well as its transparency.

“It keeps us intimate with our projects and able to make tweaks immediately,” she says. “I think we can offer such an amazing donor experience because we do everything: the fundraising, operations and implementation. This is not very common in water charities. I’m constantly inspired by the people who donate their money and time to Well Aware.”