Joan Brennecke, the first female professor of chemical engineering at the University of Texas, has charted her own career course.

Story and Photos by Sarah Holcomb

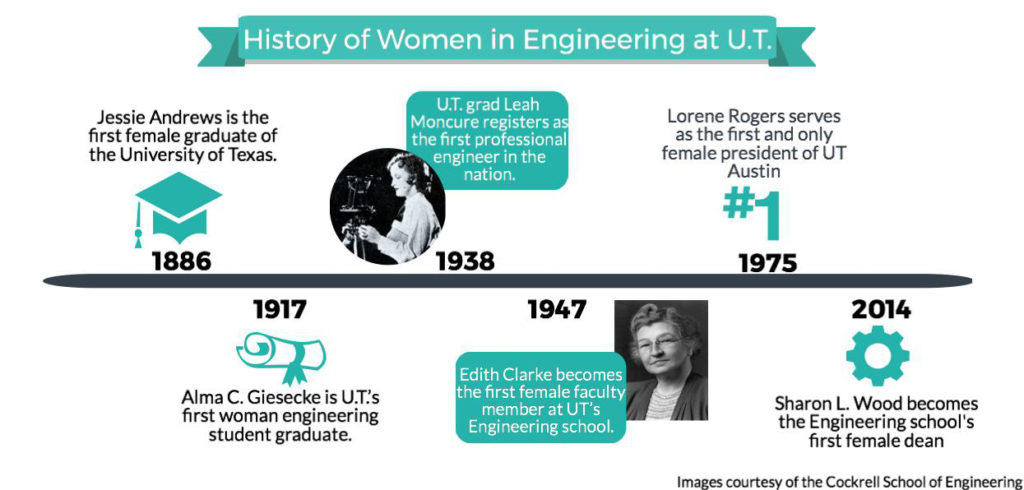

As a chemical-engineering student at the University of Texas in the 1980s, Joan Brennecke learned more than formulas and chemical processes; she learned how to stick up for herself. Some professors supported Brennecke in her engineering ambitions, helping her become more assertive and self-assured. Meanwhile, others represented the challenges she would face throughout her career in a male-dominated field.

Brennecke remembers casually chatting with a UT chemical-engineering professor about her career ambitions at a party in 1984, when he surprised her with a mocking laugh.

“A female faculty member in chemical engineering at the University of Texas — over my dead body!” he declared.

After a $2.5 million governor’s grant returned the world-class researcher to her alma mater three decades later, Brennecke can’t help but laugh at the story’s irony.

“I try never to whine about others’ behavior,” says Brennecke, now UT’s first female full professor in chemical engineering. “I tend to ignore it and do my thing.”

Engineered to Succeed

Brennecke knew chemical engineering was her thing since early high school. She recalls hours spent in the garage with her father, a chemical engineer with a Ph.D., taking apart anything the two could find. When she was 12, they disassembled a massive mechanical calculator he brought home from his job at Alcoa.

Engineering runs in the family: Brennecke’s uncle works as a mechanical engineer, her mother is a secretary for an engineering company and three cousins ended up in engineering-related positions. Brennecke entered the family hall of fame as its first female engineer.

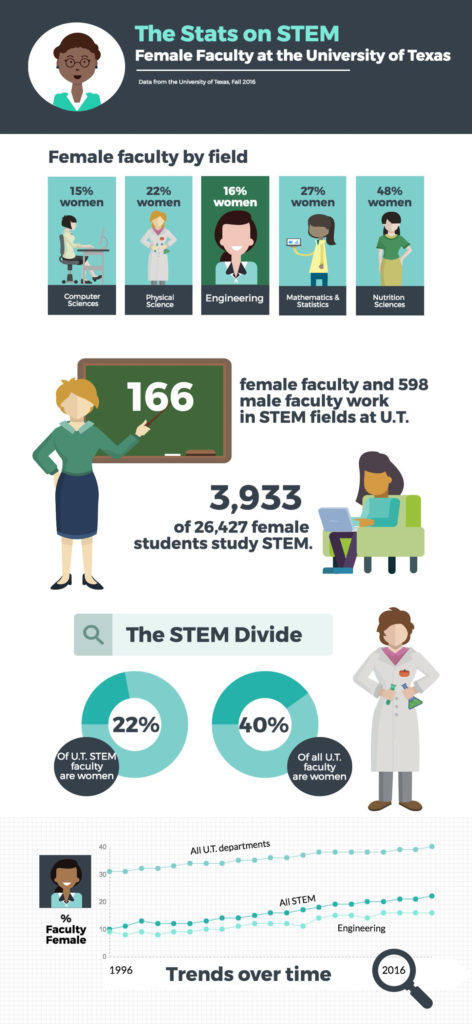

Today, women earn about 20 percent of all engineering degrees. When Brennecke hit high school in the mid-1970s, women earned just 3.4 percent of those degrees.

“My father had always told me that I could do whatever I wanted,” she says. “And I believed him.”

This spirit of aspiration drew her to the University of Texas. Attracted by UT’s high-achieving students and metropolitan campus, the ambitious freshman fit right in. Though the university had no female professors in chemical engineering at the time, it didn’t bother her.

“I didn’t really expect there to be women faculty members,” she explains.

Just Say It

Brennecke fondly remembers class with John McKetta, the UT chemical-engineering department’s legendary namesake. McKetta’s infamously interactive teaching style forced students to stay on their feet.

“He would just put you on the spot all the time,” Brennecke says. “There was no taking notes and figuring it out later. You learned in real time.”

For some female peers who preferred to stay quiet, McKetta’s approach proved especially intimidating. But when a female student once suggested the professor must dislike women, Brennecke disagreed.

“He’s not picking on us,” she said. “He’s trying to get us to be more assertive, to not be afraid. If you think of something and it makes sense to you, then say it!”

Learning to assert herself served Brennecke well during difficult and awkward situations she’s faced throughout 28 years of teaching in a largely male-dominated field. At the University of Notre Dame, she worked as the first female professor in the entire engineering program, one woman in a sea of 100 men.

“I’ve kind of gotten used to guys,” she jokes.

People walking by her office, located next to the department’s main office, would frequently pop in, assuming she was a secretary. Some of her male colleagues unwittingly made offensive comments, unsure of how to interact with the first female in the department.

“The main thing is to not assume that people are [ill-intentioned] because most are not,” she says. “But when they are, you need to stick up for yourself.”

During Brennecke’s first year teaching, a longtime professor tried to take advantage of the new faculty member and her female research student. Hoping to gain another publication with his name at the top, he threatened the student with a C grade for her semester project unless she stayed to help him with research during the summer, an arrangement that would siphon money from Brennecke’s budget, not his.

“He thought he could bully us, two women,” Brennecke says.

When Brennecke approached the department chair, explaining she needed the student to help as she started her own research, he told Brennecke to deal with it herself. So she did.

“I felt pretty uncomfortable as a new little assistant professor talking to a full professor,” she remembers. “I went to him and said, ‘This is not right.’ ”

As a result, he backed down and raised the student’s grade to a B.

“You have to look out for yourself,” Brennecke says. “You have to speak up for yourself and be confident in who you are and what you believe and what you think, what you’ve calculated. I think I’ve learned that from McKetta.”

Power By Performance

Today, McKetta’s teaching influences how Brennecke runs her own classes, encouraging students to speak up.

“She’s very demanding of the students, but in a good way,” says Edward Maginn, the current chair of Notre Dame’s chemical-engineering department.

Among her Notre Dame colleagues, Brennecke was known for more than her friendly smile and ability to easily strike up conversation over coffee. She’s known for the extensive, well-funded research operation she established.

Internationally recognized for her research in energy and sustainability, Brennecke uses ionic liquids, or salts with low melting points, to develop more environmentally friendly solvents that would improve a host of processes, like reducing CO2 emissions at power plants.

“She’s really world-famous in the area [of ionic liquids],” Maginn says. “So, she brought a lot of notoriety to the university.”

As Brennecke secured research grants—including a $2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy—as well as published more than 130 research papers and accumulated more than 13,000 citations, she solidified her reputation.

“You gain power by your performance,” she explains.

The Future Is Female

Now, Brennecke works to shift the status quo in chemical engineering. When she was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 2012, Brennecke estimates that about five women and hundreds of male colleagues belonged to the Academy of Chemical Engineering. Within the last three years, the Academy of Chemical Engineering has elected 43 women, and Brennecke now chairs the Peer Committee, which selects future members.

UT’s chemical-engineering department has also undergone a metamorphosis since Brennecke’s days as a student.

“It is much more cosmopolitan, not so much good ol’ boy,” she says.

Brennecke eagerly anticipates collaborating with her fellow faculty members. Like her undergrad self, she’s excited to feel the pulse of life on U.T.’s urban campus. And, of course, is excited to meet her students.

Gabriela Avelar Bonilla, one of Brennecke’s Ph.D. students at Notre Dame, says Brennecke serves as a valuable resource for women in engineering.

“In a field that [is]usually dominated by men, it’s important to have role models that you can relate to,” Avelar Bonilla says, “[especially]someone like her because her career is very impressive and she is a good mentor.”

When paired with a female mentor, female engineering undergrads feel more confident, motivated and less anxiety, according to a study published earlier this year.

The first piece of advice Brennecke offers female engineering students is to focus on doing their best.

“There’s no substitute for competence,” she says.

“And for goodness’ sakes, don’t ever be dissuaded or even irritated by somebody’s stupid comments or what somebody does. Don’t waste your brain cells on them. Spend your brain cells on doing what you’re doing well.”