If you miss the golden age of girl groups, Austin City Limits Music Festival is your chance to get back on the bandwagon.

By Brianna Caleri, Photos in graphic via Instagram, Joseph by Louis Browne

Name six girl groups that are relevant in mainstream music right now. It’s difficult. Haim is the hot group of the past couple of years: three sisters delivering cool pop hits featured in movies and TV, but still on the alternative side in terms of radio play. Fifth Harmony, the X Factor favorites who made a name for themselves much like One Direction, were promising before Camila Cabello broke out as America’s sweetheart. The Dixie Chicks, notorious for their bold rejection of that kind of adulation, have been playing with pop heavyweights like Beyoncé and more recently, Taylor Swift, but peaked in relevancy in 2003 with their infamous Entertainment Weekly cover.

Between the three groups, music followers can construct a diverse cross section of industry tropes, triumphs and bad habits. So why are girl groups relegated to the margins, where they’re presented as frivolous, a cookie-cutter example, at best, for young female fans to grow out of? If you miss the golden age of girl groups, Austin City Limits Music Festival is your chance to get back on the bandwagon.

Joseph by Louis Browne

The first all-women offering on the lineup is Joseph, a folk pop band of three sisters that create uplifting, momentous anthems by contrasting roaring highs with sultry lows. They’re joined on the lineup by Ley Line, a quartet (including one set of twin sisters) that plays cool Brazil-inspired originals and folk tunes around the world. The Aces start steering away from folk; the two sisters and their bandmates (four sharply dressed women in total) deliver bubbly, groovy dance music with more than a hint of irony in their music videos. And in case that’s not enough sisterly love, The Beaches—another group of four with two sisters—enter the scene with their own music-video excellence, superb style choices and an edgier, high-energy punk vibe.

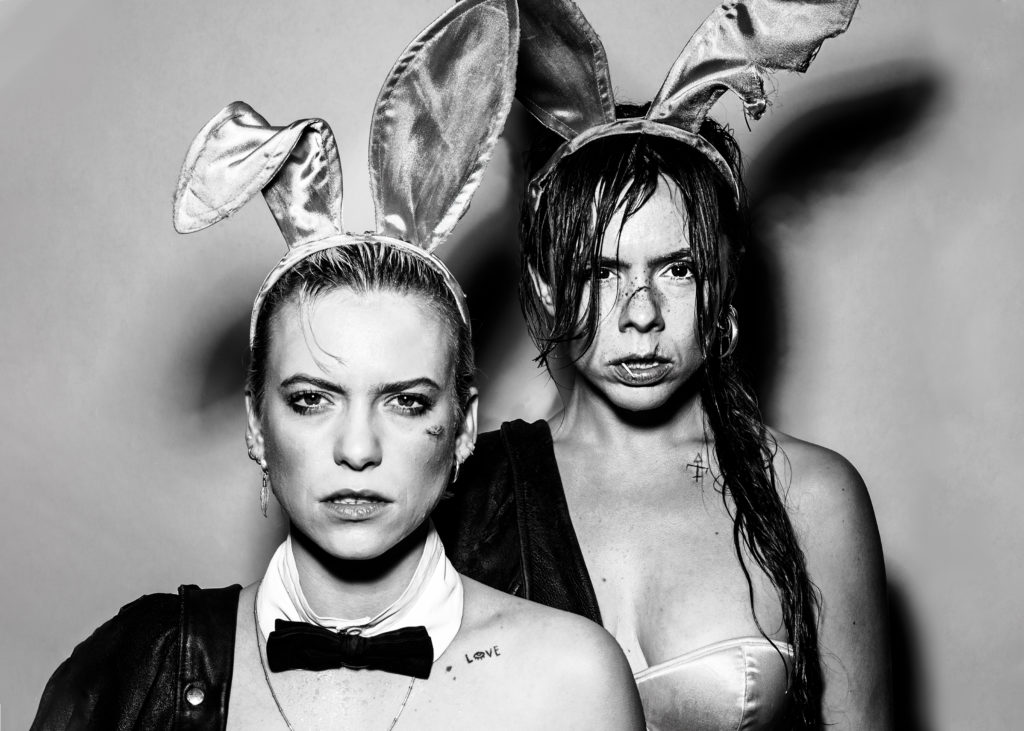

Two more bands without blood relations finish up the girl-group lineup and the punk vibes: The Aquadolls, one of ACL Fest’s more aesthetically adventurous girl groups this year, bouncing between surf rock, grunge and punk, and Bones UK, two London guitarists with a garage-rock aesthetic, who appear visibly dirty but glamorous in men’s clothes and dripping defiant sex appeal.

Is it a coincidence that four of the six girl groups on the lineup are sisters? According to the history of girl groups, probably not. In the beginning of the format, when music execs realized all-women bands were incredibly marketable as charming, wholesome entertainment, there were the Andrews Sisters. The swing trio became famous in the ’40s, singing in close harmony with a jazz orchestra and appearing in matching outfits that often included military costumes and lots of saluting. Then in the ’50s, the Chordettes followed suit, finding success in traditional pop with hits like “Mr. Sandman” and “Lollipop.” With matching outfits and barber-shop arrangements, the women were more or less interchangeable, an early example of the homogeneity and interchangeability of artists working within “hit factories” in the ’60s that manufactured radio success. The formula was simple: lovely ladies in matching dresses who could sing on-key.

Soon girl groups exploded in popularity, producing endless hits penned by songwriters in high demand, like Carole King and her husband, the lyricist Gerry Goffin. Songwriters would churn out single after single and assign them to whoever could be bothered to sing them. The Ronettes, two singing sisters and a cousin with beehive hairdos, reached iconic success with the super-producer Phil Spector, becoming the face of girl groups at the time. Named after its lead singer, Veronica, The Ronettes took a more modern approach with clearer distinctions between roles. The Shangri-Las, two sets of sisters, took a similar approach, but with darker and more soulful results.

Jordan Miller of The Beaches explains the sister musician phenomenon through “blood harmonies,” the concept that siblings can create a smoother vocal blend when harmonizing. Miller started playing the guitar a year before her sister Kylie Miller, and the two would practice together at home. They later played in a band with brothers but found that their creativity flowed more freely with other women when they joined The Beaches. Ley Line’s Kate Robberson agreed that singing with other women “totally changed the game,” and her bandmate Madeleine Froncek also found that she could sing in a more comfortable register when singing folk songs written by women instead of men.

Perfectly blended vocals are not the sole secret to great music, and a broader explanation may just be that sisters often discover their talents together and have years to hone them. Bands of brothers are not uncommon either. Plus, signing an entire group at once is often logistically advantageous for labels.

While the Chordettes may not have had a lasting influence in the songwriting process, groups of sisters now find that creative collaboration comes easier when you’re beyond comfortable with your bandmates. Joseph’s Natalie Closner Schepman calls it “a sense of abandon.” She also adds that sisters won’t let each other off the hook too easily.

Ley Line courtesy of Ley Line

In the ’60s, Motown Records took notice of the commercial success of girl groups. The label carried significance as the first truly mainstream black music enterprise (read: accessible to white audiences), and when it seized on the girl-group trend, it created a niche dynasty. The Marvelettes cemented Motown’s influence with the label’s first No. 1 hit, “Please Mr. Postman.” Soon after came one of the most famous girl groups of all time—the group that inspired the Broadway musical Dreamgirls—The Supremes. And from their ranks descended the disco goddess Diana Ross.

The days of carbon-copy close harmony singers were over. Motown continued on with rhythm and blues groups, while the ’70s spawned Heart (primarily featuring Ann and Nancy Wilson on voice and guitar) and ABBA (featuring Swedish singers Agnetha Fältskog and Anni-Frid Lyngstad). Soon divas like Donna Summer, Cher and Debbie Harry took center stage; girl groups were old news and in need of a makeover to stay relevant.

Rock music started embracing rebellious female singers who were the antithesis of well-behaved girl groups of the past. The demand for women in rock extended almost exclusively to singers; the need for a woman’s voice can’t be easily filled by a man, but that same unique need does not apply to instruments. Some male glam rock bands—most notably the New York Dolls—appeared in drag, but despite owing their freedom of expression to the women they borrowed from, they were still usually lewd and misogynistic.

Girl groups had been marketed as rock ’n’ roll before, but were deemed inauthentic to the genre by rock fans gravitating toward less polished groups toward the end of the ’60s. In 1971, an all-female rock band called Fanny broke onto the Billboard Hot 100 at No. 40 with “Charity Ball.” Fanny didn’t enjoy lasting success as a classic-rock staple, but they were pioneers in the future girl-group format that shifted the focus from singers to instrumentalists. The Runaways (featuring the teenage guitarist Joan Jett) took the baton and ran straight into one of the most iconic rebel-girl songs of all time, “Cherry Bomb.” The Bangles, onstage in miniskirts, sold even more hits in the ’80s, including “Walk Like an Egyptian” and “Manic Monday.” Finally, in the ’90s, Hole (featuring guitarist Courtney Love) cemented the countercultural potential of majority-girl groups (The group included male guitarist Eric Erlandson.) with its grungy, aggressive style and defiant feminist lyrics.

Bones UK by David Solorzano

Most girl groups active today are following this more autonomous career path, enjoying the freedoms of glam rock, punk and alternative music. The Aquadolls’ keyboardist and bassist Keilah Nina loves the New York Dolls and sees the group as a beacon for challenging stereotypes along with bands like Kiss. While women are offered more opportunities for embracing glamor onstage, they often pay for it as audiences dismiss them as shallow or inauthentic. Lead singer and songwriter Melissa Brooks points to a song from the Aquadolls’ catalogue, “Suck On This,” detailing an onstage interaction where a man makes fun of her heels and tells her to get off the stage.

“When we show up to a venue, sometimes sound people—or people at the venue—they don’t take us seriously,” Brooks says. “They think we’re just groupies or friends with the band.”

Bones UK, the most grungiest of the ACL Fest girl groups, has little to say. It’s a surprise given their deliciously disdainfully feminist lyrics and gender-bending music videos. (In one video, vocalist Rosie Bones and guitarist Carmen Vandenberg play for a group of hysterical boys.) This is what alternative girl groups worked for: the ability to be in a rock band, no explanation needed. The women list Stephen Tyler, Prince and David Bowie as influences along with Sister Rosetta Tharpe (the godmother of the blues) and hope they can inspire young people, regardless of gender, in the same way.

Despite the rise of less polished bands, the ’80s also saw the Pointer Sisters continue down the more traditional road of R&B singing groups, with hits like “I’m So Excited.” Over the years, R&B had undergone a shift from the blues to disco to something entirely new. As the genre became more entwined with rap and hip hop, Salt-N-Pepa started making waves with hypersexualized lyrics and confident stage choreography. Their 1987 song “Push It” made the trio (Salt, Pepa and DJ Spinderella) the first female rappers to be certified platinum.

The decade-or-so that followed was, to many, the golden age of girl groups. TLC, radiating confidence, scored four No. 1 singles, including “No Scrubs” and “Waterfalls.” The Pussycat Dolls, formerly a burlesque dance crew, outdid both TLC and Salt-N-Pepa in performative sexuality but with a fraction of the critical acclaim. Spice Girls presented a more family-friendly aesthetic with a cast of five stage personas that were shockingly well-balanced in popularity. In 2019 the BBC listed the breakout single “Wannabe” as the all-time highest-selling single by a girl group. In 2016, Spotify announced the track had been streamed on their platform for the equivalent of 1,000 years.

One quartet took a decade and a few personnel shifts to finally achieve breakout success in the new millennium. Reduced to a trio of independent women, Destiny’s Child released the album Survivor, which included the tracks “Independent Women” (Parts I and II) and “Survivor.” Perhaps too independent, the women crumbled under the weight of their success, and in a Diana Ross-like, industry-shattering move, Beyoncé Knowles exited the group to become one of the most successful artists of any genre or gender.

The Aquadolls courtesy of The Aquadolls

The Aces courtesy of The Aces

Any band has to wonder how many people can share the spotlight, but in girl groups the question is particularly salient. It’s difficult to market a band without a clear leader. In the entertainment industry, where divas and showstoppers are particularly valued and every woman must be the first or the best to avoid the condescending “bubblegum” label, there is incredible pressure to compete with every woman sharing the bill, including her own band.

“It can feel like there’s not enough space for everybody,” says Meegan Closner of Joseph.“It can feel really competitive within women in the industry sometimes, because you’re like, ‘Oh, no, this is my space; you can’t have it. I don’t want you to threaten it.’”

Her sister, Natalie Closner Schepman, calls it a “scarcity mentality.” The trio, like any band, has had to rely on external support to get on stages in front of bigger and bigger crowds. They’ve found that men are most likely to “take chances” on the band—most likely because women have had to guard their own opportunities more carefully. Still, the band found a valuable female mentor in Kanene Donehey Pipkin, the vocalist and guitarist for fellow folk band The Lone Bellow.

Men will have to take chances as long as they’re occupying the majority of higher-level positions in the music industry and women will have to continue reminding themselves they deserve opportunities. Strong female role models speed up the process. Vocalist Lydia Froncek of Ley Line reminisces about an early band of hers inspired by Spice World (the Spice Girls’ 1998 movie). Even so, young girls who don’t see themselves represented onstage need not worry. The Aces’ drummer, Alisa Ramirez, says the band aspired to be like the “female version” of the boy bands they idolized as kids. The group realizes they have a responsibility not only to entertain, but to start changing the shape of the industry from the inside.

“We forget that it’s not just about being onstage,” says singer and guitarist Cristal Ramirez.

The Beaches by Felice Trinidad

The six girl groups at ACL Fest listed influences from across the musical spectrum: men and women, bands and solo artists, famous and familial. Of course, musicians don’t choose who inspires them, and they don’t limit their influences to strong sources of girl power. More surprisingly, given the shame boys often endure for liking “girly” pursuits like playing with dolls and wearing women’s accessories, the bands reported male fans of all ages, along with the more predictable demographic of teen girls. The Aquadolls refer to their fans as “sweet angels,” and every other band expressed gratitude (or at least wonder) for their very diverse fan bases. Women sticking their necks out throughout history–either dressed to the nines and sold to the masses or blazing their own, contrarian way–have made it possible for the girl groups today to be, very simply, popular and successful bands.

As women make strides through the mainstream, we sit at the cusp of the ’20s wondering what will define the decade this century. In music and in life, women live in a dichotomy of making choices as women and making choices as people. Girl groups—who may rather be called what they are, bands—must inevitably keep inventing ways to push through this dilemma. It’s important to remember that every choice those women make through their voices, their guitars, or their laptops, is as both women and people. You don’t have to make femininity a part of your music, but we should thank the people who make it a cool thing to do.