Installation artist Beili Liu highlights the power of woman’s work and the red threads that connect us all.

By Cy White

The conversation is casual. Less a question/answer exchange than a trading of thoughts, ideals, experiences. From it, one gleans who Beili Liu truly is as an artist, a woman, an entrepreneur. Of course, it’s odd to think of artist as businessperson. But Liu visualizes the definition in its barest forms. “Building things up from nothing,” she says. “Let me just dig in and work hard and build something. From that small thing I build it up to something I can be proud of.

“The burden of the word entrepreneurship is that it sounds commercial,” she continues. “That aspect of the term becomes a bit complicated to address. We were talking about networking in our professional practice class, and I said, ‘That’s a dirty word too. Let me talk to you and see what you can help me with.’ I said, ‘How about I just talk to you.’ Let’s meet people and make friends so that once we make that connection, then of course you’ll help me, and I’ll help you. Networking should happen naturally.”

This is also how she has always approached her art. Consider her installation entitled The House that Lives on the Prairie (2004), in which Liu built a livable house in Nebraska. It exhibits her incredible strength of will. Each installation Liu produces is muscular. A physical act of creation that is not unlike giving birth. “The labor becomes a necessity, but not burdensome,” she says. “Sometimes it’s really intense and it’s physically demanding. It’s exhausting, but it’s also something I need and enjoy.” Another red thread. Energy. Pouring that human need for creation into a nothingness and getting something beautiful in return.

Beili Liu, an Expression of Patience

Her works Above, Below (2003) and Recall (2006, 2010) are again powerful physical manifestations of the abstract idea of patience. “The term I think about is persistence,” she says. “The sense of commitment. Not that I decide to commit, but it’s just a need to continue. When I was building the house, it was this really deep desire of really wanting to get that house done. Doesn’t matter how much time it took. That commitment comes with this desire to offer something. As an artist eventually I want to share it with people. It’s like cooking. You need to go through all the steps so you can have this amazing thing.” Drops of water on salt brick. Strands of paraffin wax dangling from a barn roof. Patience. “Grit, if I can say it that way,” she muses.

“I tell [my students], ‘Mak[e]small promises.’ Maybe it’s only to yourself, but when you keep those promises, they just boost that sense of, ‘Okay, I can do this.’ It helps us to move along even in difficulty. How do you cope? How do you survive all the pain that comes in waves to us? You do it one day at a time. One good thing at a time, one project at a time, one bill at a time. To keep going and to build up.”

Duality

It’s the work of both the artist who in February was named the Fulbright Arctic Chair, one of Fulbright’s Distinguished Chairs programs, and the little girl from Jilin, China, watching the women in her family sew and talk for hours. “That experience became a foundation of my understanding of material and space,” she says. “Something I remember vividly is to sew multiple layers of cut cloth, to sew it so dense, it becomes so thick and sturdy it becomes the sole[s]of shoes. I think that care, that tactile quality, the texture, the stitches, I think it was carved in my head.”

Liu’s work is riddled with it. What she calls the “alien and familiar, uncertainty and hope, aggression and stillness.” Inherent in her work is also a deep-seated desire to explore this notion of “diaspora,” unpack the emotion of hyphenated national identity. “I’m still arriving,” she muses, considering the question of identity in her work. “I still very much feel like a foreigner a lot of the time. In mundane daily life, sometimes I forget. But I stop and think, ‘I’m Chinese.’ I feel in my mind, my language, the resources I pull from for my work, how I think, how I relate to others, they’re all very Chinese.

Assimilation vs. Identity

“One thing I can talk about is the process of assimilation,” she continues. “When someone first comes to this country, there’s this desperate need to fit in. The fear is, ‘I don’t belong, I don’t know what I have to offer here.’ There’s the gratitude and not being aware of discrimination, for example. You just don’t have the awareness because it’s more about putting your head down, trying to work hard, trying to make sure you can continue on.

“I think it takes time to wake up and become aware,” she says. “The process to become aware is painful. Some of that pain that’s numbed or put away or ignored that I’m not looking at, or that we’re not looking at. Now it’s coming through.”

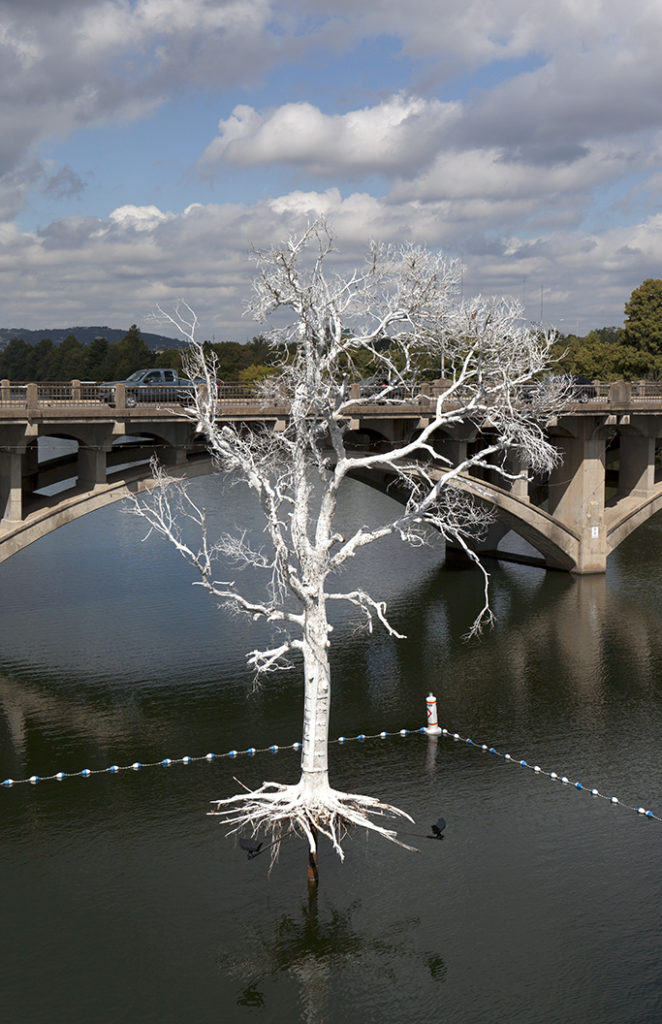

Woman. Artist. Chinese. Asian American. Immigrant. Daughter. Wife. Mother. Identity is another major aspect of what her work represents. Her Lure series (2008-17) does more than interpret an ancient Chinese story about the red thread that connects us to our soulmates at birth (a common tale in many cultures). It’s Liu taking on the physical task of telling the story of what she calls “woman’s work.” This dance between “duality” and “identity” gives very vivid form and function to her understanding of the woman as a warrior. The feminine as ferocious. “The water that can penetrate stone,” she says. “I always have to go back to it. When you talk about the strength of women, I see the dripping water as feminine strength.”

Compassionate Rage

James Baldwin said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” Liu understands that on the same level as any woman of color living in the United States. It informs her work in the most recent years, a rage mixed with incredible compassion. Her installation Each and Every (2019) is a haunting manifestation of a woman, a mother enraged with the injustice of seeing children separated from their parents. “Obviously, I’m not at the border, I’m not traveling from South and Central America trying to come into this country,” she begins. “But what I am is a mother.

Each and Every, photo credit: Beili Liu Studio

Each and Every, photo credit: James Harnois

“I’m sitting at my computer and reading the news and thinking about the kids in the cages,” she continues. “I sob. And the sobbing comes from [knowing]my kid is here. I have my coffee, my computer. My comfort. There’s such a dramatic contrast, and there’s guilt and there’s this sense of inability to help, this powerlessness. The sense of I don’t know what to do. And I say as an artist, ‘The only thing I know how to do is to work, is to make something about it.’

“This is also the piece that for the first time I’ve made a project with an object that’s literal,” she continues. “These are figures, clothing. They are exactly what they are even though they’re immersed and stiffened by cement. I asked my artist side, ‘Is this too literal?’ My human side said, ‘How else can I talk about it?’ It’s an honest response. I’m going to bring it out.

What I Really Want to Do

“That is a project where I felt it was so close to where I am and what I really want to do at this time. Run with what I genuinely feel and respond. In the last few years, there’s just been a lot of pain and [time to think]about healing. Thinking about how [to]make it visible when you have migrant children being locked in cages. They come in these cold pictures, a few articles, and then the news cycle moves on, right? I’m working, in a sense, to give you something that’s much more so you can inhale and breathe it in and be with it. It’s cold, it’s intense, it’s a very solemn piece.”

We live in a time of horrible civil unrest. The nightmare of passing day to day without knowing if you’ll survive it is a more visceral, brutal reality than the abstract notions of survival we all used to share. “This sense of survival comes in regularly,” she says. “It’s not something I talk about, but I think it’s in everything ever since I arrived here in this country. Maybe all the way to now. Through this lens I also think about other people’s experiences that I relate to. To say it in the Chinese way, ‘I use my heart to compare to yours.’”

The fight among and between ethnic groups and nationalities of color has reached levels that would make anyone shudder to think of the long-term implications. The rise in violent crimes against the Asian-American community (particularly elder East Asians) as a result of the paranoia inherent in giving a derogatory name to the COVID-19 virus is an ugly stain on our current history. A blemish left by the white supremacist birthmark of this nation. “My recent works are all informed and triggered or energized because of what I feel and what I’ve seen as a witness of our current time.”

The Person is Political

For installation artist Beili Liu, the harsh reality of our coexistence is a thick red thread that runs a deep line through all of her work. It’s a dangerous game to play as a public-facing woman, being a voice in a movement. But as is true for all women of color, living in this body leaves little choice. “In one interview I did at the earlier stage of my career,” she says, “I talk about how I didn’t want to be political, nor did I want to talk about feminism. At this time in my life…I’m welcoming and embracing all of that. It’s this arriving to become bold and to be willing to say, ‘Yes, okay. My recent work has become more political.’

“My dear friend Kay Whitney, who’s an artist and a writer, we were having this conversation. She reminded me of this sentence: ‘The personal is political.’ My work is about the personal and it is about the political. I accept it and I embrace it. It’s a time where I want to work and be unapologetic about what I’m making.”

After All / Mending The Sky,

photo credit: Beili Liu Studio

Amass, photo credit: Beili Liu Studio

Light As A Feather, photo credit: Blue Way

Recall, photo credit: Beili Liu Studio

THIRST, photo credit: Beili Liu Studio