For more than 30 years, PODER has celebrated Mother Earth and fought to protect her resources.

By Samantha Greyson, Photos courtesy of PODER

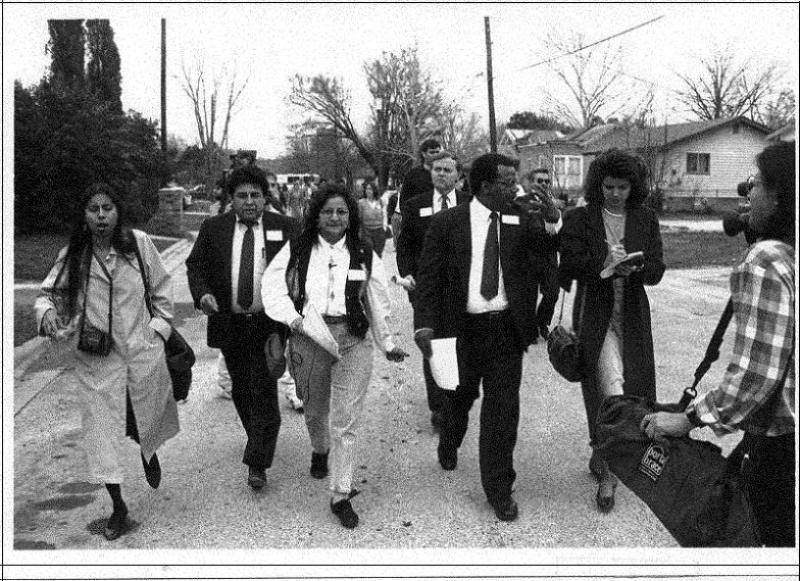

There’s an old grainy black-and-white photograph from the early ’90s. A young woman with a determined face clutches papers as she walks through an East Austin neighborhood accompanied by city officials and a news crew. This is the Toxic Tour of February 1992. The woman in the photo is a young Susana Almanza, environmental activist, politician and co-founder of People Organized in Defense of Earth and Her Resources (PODER), an Austin-based organization founded in 1991 by a group of dedicated Chicana and Chicano activists. PODER was created out of a need to fight environmental degradation, which disproportionately affected BIPOC residents of East Austin communities.

“These industries were negatively impacting the health of our residents,” Almanza says. “We decided the first thing we need to do is protect the health of the children and the elderly. Our whole goal is to close down the most polluting facilities because [they]are causing a lot of health harm, and even cancer, in our community.”

The Toxic Tour was PODER’s attempt to take on the eminent task of relocating a local tank farm, which was made up of over 52 acres of waste from oil companies like Exxon, Mobil and Chevron. These fuel storage tank facilities sat in East Austin for more than 35 years, ravaging the land in the predominantly Latino and African American neighborhood. In 1992, when PODER discovered these companies had violated air emissions regulations (thus contaminating the groundwater in the surrounding area), they joined forces with the East Austin Strategy Team and took action.

For three decades, Alamanza has actively engaged with local and national government entities, taking the fight for environmental justice right to those who make decisions that impact the general population. In 2021, Almanza was appointed to the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, formed by President Biden and Vice President Harris. Almanza’s appointment aligns with the work she and the women of PODER have done for decades, work that has seen them challenge major companies for the harm they have caused East Austin communities.

For PODER co-founder and East Austin native Dr. Sylvia Herrera, ferocious activism is nothing new. She’s been in the trenches since she was a child. “My parents, along with other elders, provided a foundation for us to see the beauty of the environment surrounding us in East Austin,” she says. “The family home is in East Austin on Oak Springs Dr., where natural springs still run. The pecan groves, the flowers and gardens were all important parts of our lives. My mother always composted and taught us to turn off the lights when you leave the room. To this day, at the age of 93, she reminds us to conserve energy.”

Herrera has known Almanza since high school. They were both involved in Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers movement. “Cesar Chavez and Delores Huerta were concerned about farmworker issues, including the products that we were consuming,” she says. “I began to see the connection between health and the environment, the spraying of pesticides on our food and farmworkers.”

For PODER, Herrera uses her specialty in health education to examine the health impacts of industry and pollution on the families living in East Austin communities.

Family is what led the members of PODER to first become involved in the cause. The women of PODER all have families—children and grandchildren—who motivate them to protect the community and environment for future generations. Today, the women reiterate that their focus is on the challenges facing East Austin. Everything leads back to the community.

“As a resident [in East Austin], at the time I was a single parent,” Herrera says. “[My] two children were small, so I was concerned about their safety. I had been complaining about heavy industrial trucks that were parked along Springdale, right across from my house. There were a lot of reasons for becoming involved, not only on a personal level, but also just a commitment to working on the issues. My interest has been trying to inform the residents in terms of how these facilities might be affecting your health.”

For board chair Janie Rangel, the issues PODER takes on quite literally hit close to home. She became involved in the organization to stop the negative health impacts of the tank farm she lived right down the street from.

“When PODER went door to door checking on people, they realized there were so many people in that neighborhood, right behind where the tank farm was, who were dying of cancer,” Rangel says. “[The community] didn’t even know it was there, and that’s probably the reason they got cancer; they were living right there.”

Rangel remembers several instances where the city demonstrated negligence toward her neighborhood and its safety. For instance, she found lead, which had washed downstream from the tank farm, in her backyard.

“At the time, I had a 2-year-old son, and we had to go to have him checked out, because of all of that lead,” Rangel says. “He used to play in the backyard, and of course he would play with his hands. He started getting sick, and the city had to come out here. They dug up my backyard to get all the dirt that was contaminated. Had I not seen what was going on in the backyard [and reported it], there’s no telling what would have happened to him. They just can’t do that, just dump stuff anywhere.

“They finally closed it down, thank God for that,” Rangel continues. “But [from then on], the people wanted to be included. They wanted to say, ‘This is my neighborhood; I’ve got to do something.’ With PODER, we were able to get the community involved.”

Along with their philosophies on Mother Earth and how to protect her, PODER follows the Indigenous model of elders as leaders in the community.

“We developed a one-page survey that’s been used on various issues,” Herrera says. “We’ve done [one]on transportation and on different things as a way to solicit conversations and to also gather information on what’s happening in the community. That’s something that people have responded to.”

Consequently, their research and outreach to the community led them to discover that unclear zoning laws were dictating where these harmful facilities were placed. “We were looking at the biggest industrial facilities in our communities,” Almanza says. “How do we get rid of these facilities that are negatively impacting our health and the environment?”

Zoning dictates the types of land use the city allows within certain commercial or residential areas. It is also a huge issue when it comes to environmental degradation negatively impacting low-income communities. PODER educates East Austin residents on how to read and understand zoning notices. Their urging the City of Austin to make notices more easily intelligible for the everyday person prompted officials to begin publishing zoning notices in Spanish and English.

“Land use issues are passing in our communities because [East Austin is] designated as the desirable development zone,” Almanza says. “The City promotes all industry and the commercialization [and]high-density zoning in our communities, so we’re constantly battling these zoning cases because they come in as so-called ‘affordable,’ but they’re not affordable at all for our community.”

To protect the housing of East Austin residents, Herrera suggests that the city could put a cap on property tax for long-time residents, some of whom have lived in the area for decades.

“When you have a housing crisis, but you’re destroying affordable housing, or at least access to stable communities or a stable environment, then you’re not only destroying the fabric of a community or neighborhood that’s well established, but you’re destroying the future generations of residents,” Herrera says.

Changes to zoning facilitates increased construction and commercialization in East Austin. This not only impacts affordability, but the surrounding environment. Almanza emphasizes the ability of soil to break down pollutants through microorganisms, so with the increase of concrete comes the increase of polluted runoff.

“Earth has a way of digesting all the pollutants,” Almanza says. “The way it is now, you’re getting [pollutants]into the creeks because [the ground is]all cement. The earth isn’t able to go through its natural process because it’s all covered. Now you have all of these pollutants going into the streams; whether it’s creeks or the rivers, it’s runoff. It’s not following a natural process. If you look into all Indigenous knowledge, you don’t want to pave the earth. When you’re just paving over everything, the earth is not really breathing.”

Environmental degradation disproportionately impacts communities of color. According to a study conducted by the National Library for Medicine, Native Americans have the highest mortality rates as a result of natural disasters, followed by Black communities. This highlights the importance of PODER having a seat at the table when the City makes decisions regarding East Austin.

Almanza adds, “By going out into the community and talking to people, there’s a way to organize and say, ‘We need to get this changed’ and ‘We need you to speak on this.’ We don’t ever do anything on our own; we always work with our community. As a matter of fact, our board of directors is not the traditional Western philosophy of boards, like CPAs and lawyers. Our board members are all chairs or presidents of their neighborhood associations.

“It’s hard for communities to be involved in a lot of the bureaucracy, talking to City Council [or]going to meetings, because they’re at work,” she continues. “That’s the role that PODER [plays], and if there is research to be done, we’ll do that as well.”

That research includes gathering information about the environment in the surrounding communities. PODER is currently conducting an air quality survey of the community living near the TESLA plant. In 2021, the electric car company opened Gigafactory Texas on Pickle Parkway just outside East Austin.

“When you go out there you’ll find these other issues as you talk to people,” Almanza says. “We found out they’re having to pay double for water because they have private companies instead of the city providing the water. But again, these are low-income, working communities of color. You, again, see that disparity and that racism that has locked them into that state.

“A lot of times people are not informed of the goings-on or what the process is, in terms of city politics or the city processes on zoning or planning,” she continues. “A lot of times it’s very basic information, so when PODER works with a community we provide as much information as we can regarding the issue. Once people are informed, they will take action, they will participate. But it’s just taking the time to inform them as to different ways that the issue can be addressed, say before the City Council or before the Planning Commission or before the different entities that are dealing, or not dealing, with a problem.”

The recent increase in winter storms in the past few years brought to light another major focus for the organization: solar energy. PODER is in the process of attempting to create an Austin industry based in solar energy to provide jobs and reliable, affordable energy for low-income communities.

“We had people with toddlers and infants who were completely in the dark and cold,” Almanza says. “The warming center was closed; it turns out that it didn’t have any generators, so we bundled up to go there, and it was like, ’Oh my God, it’s closed!’ No one had anywhere to go. One of the things we were saying is we need to have a solar hub and install solar panels in the most vulnerable communities that need it the most.”

The women of PODER constantly reiterate that the work they do is not about them; it is about the community. Their humility drives the energy behind their activism.

The East Austin community was there for Herrera when she was finishing her dissertation to graduate with a Ph.D. Without the support of the community, Herrera insists she couldn’t have finished. She wants to support the community that has supported her, her whole life.

Rengal continues to do this work “because [she]enjoys working with and protecting the community and the people around me and giving a voice to the people who are voiceless.”

“It’s a question of preparing the next generation and the next generation,” Herrera says of PODER’s mission. “Leaving [them]an environment where they can thrive. Our approach is holistic in terms of the natural environment, the water, the soil. Mother Earth is part of our indigenous perspective and belief that all natural things should be protected. But that also includes us, the places where we live, work, play. Every living being has to be respected and recognize that we need to protect one another in terms of having a clean environment.”

This is the essence of PODER. As with much of the language surrounding the work they do, the name references the Earth and her resources. PODER {centers} Mother Earth and her importance to all living things.

“The people who founded PODER are very much grounded in our Indigenous models,” Almanza says. “We honor the earth; we honor the four directions. Traditionally, we’ve always been very in-tune about the earth and what the earth gives us and how we look at her as a female entity. How do we honor our own mothers? Do we disrespect them? Do we drill holes in them? When you’re more in-tuned that the earth is this female entity, you need to respect the earth.”

“Our elders were connected to the land and all living things and showed us to do likewise,” Herrera says. “This is the memory of our Indigenous roots, and it is our responsibility to carry this forward for future generations.”