Forklift Danceworks puts blue-collar workers in the spotlight.

By Brianna Caleri

In graduate school, Allison Orr watched a man clean some windows. The former social worker was studying choreography at the time and had spent the whole day in the studio. The campus foreman, Manuel Godinez, faced her from outside and swept his tools across the window with ease and forethought.

It was 1998, so there were no “satisfying” viral videos of perfect window cleanings yet. There were no TikTok dance challenges to interpret real life into something consumable in seconds. But pattern recognition is universal.

“I watched him and thought, ‘Well, that’s the most interesting choreography I’ve seen in a long time,’” Orr recalls. “There’s a very specific pattern to his window washing. It was very clear and precise. It was absolutely rehearsed. And it was very determined in terms of timing. It was all that you want a dance to be.”

She approached Godinez to introduce herself and explain a performance series she’d been working on. Collaborating with campus employees, she choreographed routines to mimic their everyday activities. The foreman agreed to perform his solo. To this day, Orr remembers his dance and “generosity” as emblematic of her goals as a choreographer.

“The gorgeousness of the movement, the perfection of that dance….It’s still what I’m doing,” says Orr.

For Beauty

The choreographer built a career on curating this type of movement and encouraging manual workers to perform it. Not for utility, but for beauty. Most of her choreography is dominated by self-presumed non-dancers. Her company that runs on the contributions of these community members, Forklift Danceworks, celebrates its 20th anniversary this October.

When Forklift approaches new performers, its first task is to start chipping away at doubt. “My favorite group to pitch to are highly skeptical men,” Orr says with a laugh. “They’re so fun, and they’re so easy to shock.”

It must have been surprising for Godinez to hear someone was enjoying his menial task. Thankfully, if he felt any self-consciousness, he transcended it. The transition from worker to dancer, in these cases, is entirely mental. There are no complicated moves to learn, no strenuous flexibility to attain. The turning point for many participants comes when Orr explains to them that they are simply doing their jobs to music. The pride of getting a job done with no fuss stops being an obstacle, and pride for what is often a lifelong career takes over.

“Once they see that we’re really operating in their own vocabulary, they then want to raise the bar and make it great,” says Orr.

Krissie Marty Meets Allison Orr

Allison Orr with The Gondola Project poster in Venice, 2003.

Photo courtesy of Forklift Danceworks

Krissie Marty. Photo by Penny Snyder

Krissie Marty, Forklift’s associate artistic director and community collaborations director, didn’t need any convincing on Orr’s vision. She and Orr worked—though not at the same time—for the Liz Lerman Dance Exchange (now simply Dance Exchange) in Maryland, which emphasizes community participation and has worked with entities including NASA, Facing Race and the National Park Service. Marty heard from others at the company that a woman from Texas had just left but didn’t recognize Orr’s name.

When Marty returned to Austin, she reached out to the woman she’d heard of to make a connection in the local dance scene. She accepted an invitation to a rehearsal Orr was running for the Forklift project 200 Two-Steppers on the Steps of the Texas Capitol. The large-scale dance, featuring over 300 participants, was sourced straight out of honky-tonks Orr visited. She spent four months convincing hobby dancers to sign on for a performance during arts nonprofit Fusebox’s “T is for…” event, kicking off the 2010 iteration of their annual festival.

“I think I just leaned over and said something to her about rehearsal…and probably gave her some unsolicited advice,” says Marty. “And Allison was like, ‘Oh my God, Krissie, you get it!’”

What Marty “got” is central to Forklift’s mission statement: “All people are inherently creative.”

Forklift Danceworks is Born

The dances expose overlooked workers to the communities they serve. But they also uncover an inner creative life that many people never connected with. The collaboration is the core art; the performance is simply the finishing touch.

Forklift’s best known project, The Trash Project, engaged workers from Austin Solid Waste Services in a company-defining performance attended by thousands. The partnering documentary, Trash Dance (2012), invites viewers behind the scenes, revealing the extent to which Forklift immerses itself in a community while choreographing. Orr spent twelve months coercing the workers to see themselves as worth watching. In the film, Orr appears benevolently unshakeable in her desire to simply be present, while beginning to challenge the status quo. The workers appease her but are slow to adopt her enthusiasm for the idea.

As Orr shadows sanitation workers, she balances a willingness to try each job with a girlishness that, to viewers who have been in a similar place, might seem carefully curated. There is enough toughness in the job to go around; it’s the choreographer’s job to inject some vulnerability. Every few scenes a curtain seems to lift as she becomes firmer. Not unlike a popular grade-school teacher sneaking some actual curriculum into a reluctant but emotionally devoted class.

The Art in the Work

The workers’ attitudes start to evolve in parallel. “This is just a sly way to get out of work,” says crew leader Lee Houston. After allowing himself the vulnerability to rehearse using classic slacker logic, he starts to consider the impact the show could have on his daughter. He decides to commit more fully as a way to teach her about giving back to her community.

Attitudes start to shift, and the workers start getting excited, even pitching their own ideas. They start to see past the project, to the art inherent in their work.

Absolute Bliss

“Now that I think about it…I’m pretty sure we could go out there and do a job and you could put music to that,” says supervisor Chris Guerrero.

The final production is performed in a gentle mist on a rainy night, with slick asphalt melting into the dark sky and heightening the drama. Without an idea what the dance will look like, it’s easy to predict a neat neighborhood event that someone could, theoretically, see art in. But it is art. No imagination necessary.

Sixteen large sanitation vehicles parade around to music by composer Graham Reynolds. Tony Dudley, then dead animal collector, gives a monologue about his work. Ivory Jackson, Jr. raps, and Orange Jefferson plays a soulful harmonica solo. Anthony Phillips, who earlier introduced himself as a jam skater, performed his own choreographed breakdancing.

When Don Anderson, the charismatic de facto main character from Solid Waste Services, performs his crane solo, Orr becomes visibly emotional.

Anderson’s face is overcome with blissful concentration as he guides the machine through sweeping turns. Its metallic clanging seeming to lead the live band. It is Orr’s closeness to the project bringing tears to her eyes. But there’s something else that carries the emotion through to the audience. The show is about the people, whether or not you know them apart from the vehicles. They are inseparable.

One of the last shots of the film shows supervisor Virginia Alexander waving to a child from her truck. She’s out of the limelight, back to work and basking in the purest form of appreciation most workers receive outside suddenly becoming dancers.

A Place in Dance for Everyone

Never having been a proficient enough dancer to make a career of it, Orr explains, “I always felt like whatever I was making, both my grandfather and my 5-year-old next door neighbor needed to feel like it was relevant to them. I didn’t know there would be a place in dance for me.”

Once she found it, she had to share it.

Now a bigger company with five full-time and eight part-time staff, Forklift is managing multiple long-term projects. The research doesn’t slow down just because they’re busy. Ideally, each project includes a year of shadowing to learn which actions are integral to the work, who is best at each specific job and what people don’t normally see. Then interviews are conducted to learn more about the cultural context of the work and use in clips during the show.

“We take a lot of time to learn that and to build relationships, to then have people perform. They have to trust us too,” says Marty.

Forklift Dancworks 20th Anniversary

Forklift’s 20th-anniversary project gathers more of these interviews to fully explore the jobs it has represented. The retrospective portrait series On the Job engages 20 former Forklift performers to catch up and give deeper background. From an Elvis impersonator talking about his aunt dating Buddy Holly, to a Venetian gondolier discussing his position as the last in a line of three generations with the job.

“A lot of people say that truck drivers, dock workers…that they’re the nobodies. They see us as the nobodies. We were able to see ourselves like movie stars, like rock stars,” says Liliana D’Osio of Goodwill Central Texas, crediting the Forklift project RE Source in her interview. “I see people that matter, I see essential workers. I see them, my little family, as bigger.”

Recently, Forklift wrapped up a baseball project at Downs Field, handing the community-led advisory committee to Huston-Tillotson University and Six Square for continued development and community engagement. It’s also looking forward to a performance at Connecticut’s Wesleyan University in October, featuring workers from physical plant (which handles facility maintenance) and custodial services. The rest is planning. Orr will publish a book next year with Wesleyan University Press; the company is starting a residency with Austin FC and there’s a party to throw.

The Forklift Dancworks Gala

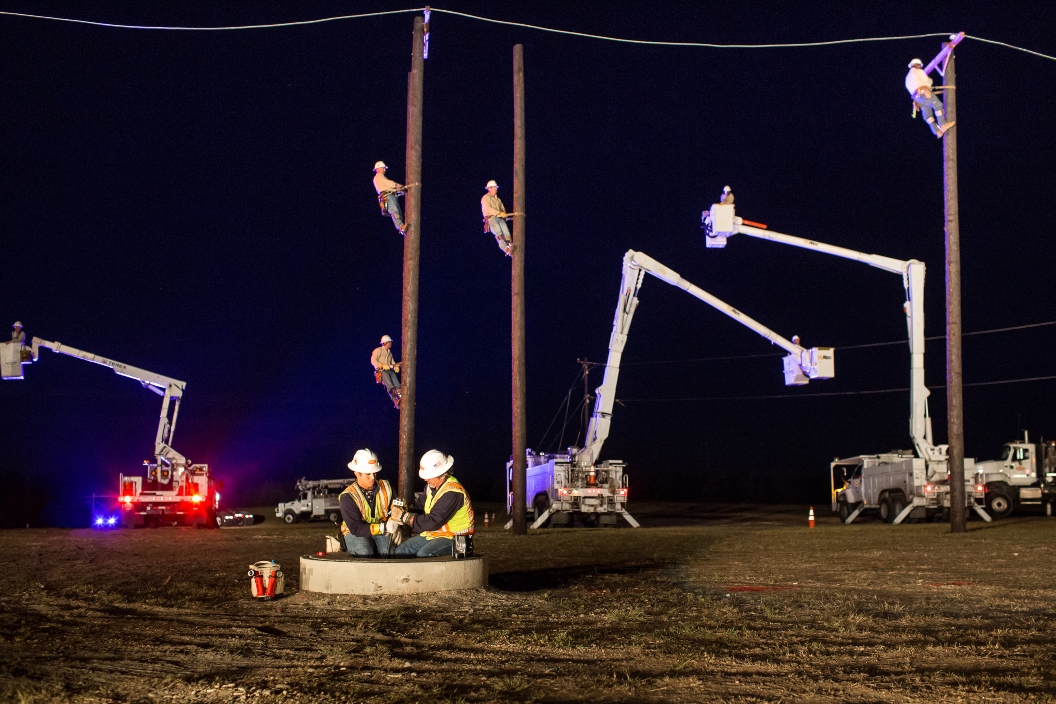

The 20th-anniversary gala, held October 28 at the Umlauf Sculpture Garden, is essentially an in-person iteration of the portrait project. It will invite community members and leaders to come together and engage with seven of Forklift’s past projects: The Trash Project; Take Me Out to Downs Field; The Gondola Project; My Park, My Pool, My City; In Case of Fire, PowerUp (featuring Austin Energy) and The Trees of Govalle (featuring Austin’s Urban Forestry Division).

Five projects will be represented at the event via booths serving themed food, drink and experiences. Current plans for the baseball booth include American food, whiskey and an athletic challenge. Some alumni from each project will work the booths, while previous performers from the remaining two projects will give short performances. Don Anderson, who joined Forklift as its community engagement advisor after his endearing performance in Trash Dance, will reprise his crane solo to close out the night.

The gala is the company’s biggest yet, with a goal of raising $100,000. Still, the gala is designed mostly as a community social event. Many Forklift supporters are dancers who look forward to networking and getting their groove on together. And as the company has proven, everyone else is a dancer, too. The company often finds new projects through alumni connections, so events that practice community connection are vital.

“So, how do we get people together in a common space who may not typically gather so we can build capacity for folks to do hard work together?” reflects Orr. “Ultimately I think what Krissie and I are working to do at Forklift is to create opportunities for people to build relationships; to listen and to develop empathy and understanding across all kinds of differences.”