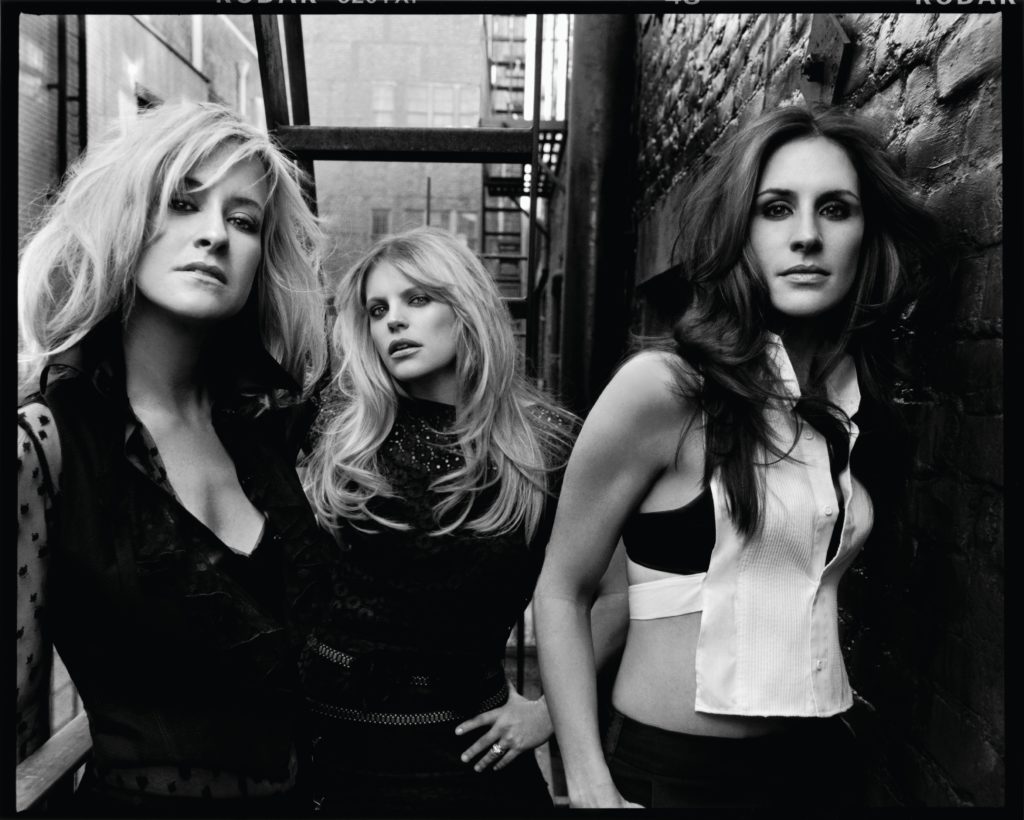

Sisters Martie Maguire and Emily Robison chart a new course, musically and personally.

By John T. Davis

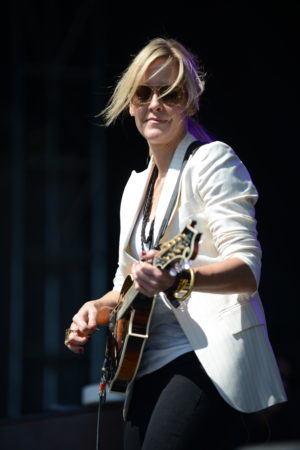

A hazy day in mid-March 2010. Two strikingly attractive women, one in a red leather jacket with her long, blond hair bound back, the other with a tumbling brunette mane framing a pair of enigmatic tinted Ray-Bans, step onto a makeshift stage at Clive Bar in the heart of the Rainey Street District. It’s another day in the open-air lunatic asylum that is South By Southwest, and this is one of scores of day parties being held throughout town.

The names of the two women stepping onto the stage are familiar, although the context in which they are playing today is not. This is the first public performance of a new band called the Court Yard Hounds. A couple hundred folks mill around, nursing hangovers and awaiting developments with a curiosity that ranges from mild to avid.

The women—they are sisters, it should be noted—are joined by two guitarists and a drummer. No bass player. There’s a loose backyard jam session feeling about things that belies the fact that this gig represents a new band, a new album and a new chapter of what Dan Jenkins used to call life its ownself.

The blond picks up a fiddle. The brunette slips on fingerpicks and plugs in a Dobro guitar. They exchange a glance, and there is the sense of an electrical relay tripping. Then they begin to play.

And just like that, one door closes and another opens.

The last time Martie Maguire—she would be the blond—and Emily Robison—that would be the brunette—officially set foot on an Austin stage for a non-benefit performance was a little more than three years previous. That show wasn’t to play for a relative handful of South By Southwest onlookers, but for a boisterous crowd at the Frank Erwin Center that come to see the Dixie Chicks, the band the sisters co-founded in 1989.

The Chicks are still a going concern; they are playing dates in Canada this fall, and appeared locally last May as part of a fundraiser for local PBS station KLRU. But Maguire and Robison have spent the past three years charting a fresh course.

Their 2010 South By Southwest debut fell on the eve of a the release of the first album from the band, the sisters’ latest musical incarnation. That self-titled album was born both out of the pain of Emily’s divorce from singer/songwriter Charlie Robison—music as catharsis—and their pent-up desire to make new music again.

Now the Hounds are back with a second album, Amelita, a multi-faceted affair painted in tones of light and shadow.

And amidst the hoopla accompanying the release (Leno on the West coast, Letterman on the East coast, GMA at some ungodly hour, Lollapalooza on the horizon, social media nonstop, the same five interview questions asked coast to coast, multiplied by a hundred), Maguire and Robison spoke to Austin Woman about the house of mirrors in which they make their lives.

Mirrors. Every time they turn around, there is a different reflection: sister, bandleader, mother, songwriter, businesswoman, breadwinner, Court Yard Hound, Dixie Chick, virtuoso, seeker, artist.

Mirrors. Every time they turn around, there is a different reflection: sister, bandleader, mother, songwriter, businesswoman, breadwinner, Court Yard Hound, Dixie Chick, virtuoso, seeker, artist.

The hat trick, of course, is to integrate all the reflections, and therein lays the challenge. That challenge was crystalized in a perfect moment one day in August. Emily was conducting a phone interview about the new album when a terrible crashing and pounding arose in the background.

“Sorry,” she explains, “my daughter’s discovered her hammer toy.” Peace restored, she elaborated on her 10-and-a-half-month-old, her fourth child. “She’s happy to go anywhere, be anywhere. She sits in a guitar case while rehearsal’s going on.”

The Hounds had been rehearsing that very day in Martie’s home studio. Emily had driven up from her own home in San Antonio to her sister’s place near Lakeway. The next day, they were due to set out for that exotic, dazzling, heart-stopping mecca of show business, Fargo, ND.

Being a working mom who happens to spend weeks crisscrossing the country has its own unique hurdles.

“My older kids are shared with their dad, and he’s a musician too,” she says. “So it’s got to be worked out. If he’s going to be out for two weeks, then I’ve got to be home those two weeks. It’s a juggle. I spend more time on my iCalendar just looking at blocks of time.”

On the other hand, her current husband, Martin Strayer, plays guitar and writes songs and tours with the Court Yard Hounds, so at least their new daughter can have both parents on the road.

Her own three kids are key reasons Martie Maguire is enamored of Austin, even though she could choose to live anywhere. The abundance of music, the lo-fi vibe around celebrities and the wealth of outdoor options make a potent combination.

“That’s the beauty of this town; it’s very artist-friendly. I wouldn’t want to raise my kids in New York or L.A., and those are two of my favorite cities,” she says. “It’s too much industry. Here, I can go under the radar and so can my kids. People are used to seeing Willie or Sandra Bullock around town, and I think they’re seen as real people with real families, and respect is given for their privacy. I like that.”

Maguire and Robison, of course, are all too familiar with the double-edged sword of overpowering celebrity, and the way a fickle public and the voracious media can turn a normal person into a frog awaiting dissection in a high-school biology class.

The story of the Dixie Chicks’ ascendency into the stratosphere to become the best-selling female band in American history, and their subsequent fall from grace after a disparaging comment about President George W. Bush uttered by Chicks vocalist Natalie Maines in 2003 is too well-known to recount in detail here.

Maguire and Robison will always have a soft spot for the band they built from scratch (they have been the constants; vocalists Robin Lynn Macy and Laura Lynch both preceded Maines).

“We’re all three very proud of what we accomplished with the Dixie Chicks,” Robison says.

At the same time, the Court Yard Hounds allows them to both grow as musicians and songwriters, as well as reset the odometer and downsize fame to a human scale.

“The Court Yard Hounds came about because Natalie didn’t want to go back into the studio,” Robison explains. “For us, it was important to continue to work and have an outlet. It wasn’t like we went off and did something without conferring with her. And I’m tickled she’s doing something on her own, so she can go off and scratch that itch.”

Maines released her first solo album, Mother, this spring.

“The Court Yard Hounds is my world and my focus,” Robison adds. “When opportunities for the Chicks come along, and we all three decide yeah, we want to do that, we’ll make that our focus for a time. But this band is where my heart is right now.”

The Hounds’ first album sold very respectably, and Amelita has been getting airplay and good reviews (it might be “the most buoyant album of 2013,” said the LA Times, and Rolling Stone cited its “haunting harmonies and summery hooks”).

Still, would the sisters willingly step back onto the roller coaster and replicate their earlier mega-success, this time with the Hounds, if they had the power to do so? Say that same fellow who approached Robert Johnson at the crossroads, the one with the pointy tail and the smell of brimstone about him, offered the women a chance to sign on the dotted line and take the ride again, would they do it?

Maguire—older, wiser—has only to look at her family to know the answer.

“I’ve lived every life I could’ve wanted to live career-wise,” she says fondly. “All the expectations and dreams and aspirations I’ve had for myself have been so far exceeded.”

“There were so many people who knew that no one’s on top forever, and there was that feeling that everyone was trying to make a buck, and not thinking about your sleep or your well-being or the psychology of going all over the world and not having time for friends and family. There were some very tough years in there,” she says. “I look at my kids now, and they’re getting to the age where they’re figuring out, hey, I like to Irish dance, or hey, I like to play the piano. And I think now’s the time for me to give back to them the way my parents gave to me. So that time is over for me—the grind. If I’m gonna grind again, I’m want to do it on behalf of my children.”

Not that being a woman musician on the road, let alone a mother on the road, isn’t always a grind on some level. “I hate it when women pretend like we have it all figured out, because none of us do,” Robison says. “It’s constant work and it’s constant compromise. I can’t tour as much as I want to and I can’t be home as much as I want to. I don’t get what I want, you know?”

They’re not complaining. This is the life they have chosen ever since they were young girls growing up in the Preston Royal neighborhood of Dallas. Emily and Martie Erwin’s parents were both educators who instilled their daughters with responsibility and indulged their early love of music.

“They weren’t stage parents,” Robison says. “They didn’t see us getting into the business. They wanted us to play in the orchestra in school.”

But Maguire started gravitating to bluegrass after her parents gave her fiddle lessons for her 12th birthday and began ushering the girls to acoustic music shows and festivals. On one of those trips, says Robison, “I saw the banjo from across the room,” making it sound like Bogey making eyes with Bacall.

“Our parents wanted us to understand the work ethic of having a job,” she continues. “So we’d get waitress or hostess jobs, but then we’d go down to the street corner and we’d make 10 times as much with our guitar case open.”

By the early 1990s, they, along with Macy and Lynch, had established the Dixie Chicks as a solid genre attraction. They wore spangled cowgirl duds and released independent albums with titles like {Thank Heavens for Dale Evans}. Lynch even had a stand-up bass guitar shaped like a saguaro cactus. Think of a way, way cuter edition of Riders In the Sky and you have the picture.

By the early 1990s, they, along with Macy and Lynch, had established the Dixie Chicks as a solid genre attraction. They wore spangled cowgirl duds and released independent albums with titles like {Thank Heavens for Dale Evans}. Lynch even had a stand-up bass guitar shaped like a saguaro cactus. Think of a way, way cuter edition of Riders In the Sky and you have the picture.

Through ceaseless effort and non-stop touring, they amassed a strong regional following at festivals, clubs and beer joints throughout Texas and neighboring states. (Their habitual stops in Austin were the Cactus Café, La Zona Rosa and the Broken Spoke).

Then, in 1997, seeking to expand their horizons and broaden their sound, they ditched the sequined skirts and the cactus bass and recruited a feisty West Texas girl with a blowtorch voice named Natalie, courted the Nashville powers that be and recorded their first major-label album, Wide Open Spaces.

And then it was off to the races: Grammy Awards. Hit singles. Multi-platinum albums. Headlining tours. Your basic showbiz fantasy. Until, as they sang in the title track to their 2006 album, Taking the Long Way, “the top of the world came crashing down.”

Years later, The Road You Take, the concluding song on Amelita, talks about living with, even cherishing, the choices one makes along the way that form the person looking back at you from the mirror.

Beginning in self-doubt (“I’ve been thinkin’ ’bout what it takes to fall in love these days. I’ve been going ’bout it the wrong way.”) and ending in assertion (“You are not alone. And you can journey on.”), the song is a sort of pilgrim’s progress, what Maguire describes as “a mission statement.”

“It’s about letting the road be what it is, and making your own choices and you just own it, for better or worse,” she says. “We’ve both had divorces and both had struggles with fertility and we haven’t always made great choices. But that’s part of the humanity of who you are. The highs and lows are all part of the journey.”

“I didn’t want to be preachy, but I do believe your destiny is a series of choices you make,” Robison adds. “Every small choice leads you down a certain road. People have to take ownership of where they end up in life. There’s a little bit of fate involved, but I think you create your own fate in a lot of instances.”

“Why the hell not?”

That’s a phrase the Erwin girls have found themselves employing a lot more as the years have moved on. Not only employing, but embracing.

“Around the time of the first Court Yard Hounds album, I was going through my divorce and I had to totally re-assess,” Robison says. “Who am I? What am I all about? Now, I’m at the point in my life where I don’t care necessarily as much of what people think about me. Of course, I want to be a good person. But as far as pleasing other people, or using people as a barometer for how I feel about myself, I feel like I’ve totally shifted on that. I’m like, you know what? Why the hell not? I came to this crossroads where I had to realize that I just have to go with my gut and my heart, and whoever wants to come along can come along.”

She laughs, in a little moment of self-realization.

“It was liberating!” she says.

“As you get older, you start saying that a lot more,” Maguire says. “I drove my kids all the way out to Marfa last September. It was a ridiculously long trip, and my kids hate to be in the car. But why the hell not? I wanted them to have a piece of what I had as a child. My parents loaded us up and drove us to these festivals. Why did they do that? How did we get this unique opportunity as kids? I wanted my kids to have that. Why the hell not?”

It was her children that afforded Maguire with a uniquely insightful and affirming legacy moment not so long ago.

“I went to a Taylor Swift concert because my girls are huge fans,” she says. “And she started singing Cowboy Take Me Away.”

Maguire penned the 1999 Dixie Chicks hit for Robison’s wedding.

(In a YouTube concert clip, Swift calls the “beautiful, gorgeous” tune the first song she ever learned on guitar.)

“And this audience, these young 12- and 13-year old girls, start singing. They were tiny when that song was on the radio!” Maguire says. “Here I am, holding my daughters and they’re looking up at their idol, who’s singing one of their mom’s songs. I just about bawled my eyes out.”

There was a unique sort of closing-the-circle moment in Austin back in May at that aforementioned fundraiser for KLRU at ACL Live at the Moody Theater. The event was a concert tribute to Lloyd Maines, the indispensible steel guitarist and producer who has appeared on more episodes of Austin City Limits than any other musician.

The evening featured a solo performance by Natalie Maines (Lloyd’s daughter, as it happens), then a set by the Court Yard Hounds and concluded with the Dixie Chicks. The end of the night saw all the musicians, along with a passel of kids and grandkids, onstage ripping through Buddy Holly’s Not Fade Away. It was a hell of a night.

Maines has known Maguire and Robison since he played steel on their 1992 album, Little Ol’ Cowgirl. He and his wife, Tina, often hosted the girls for supper when the Chicks would pass through Lubbock. And, of course, he passed along a demo tape of his daughter that led to Natalie joining the band. He also produced their multi-platinum album, Home.

He knows these women, in other words. Not only musically (“Even back in 1992, they could totally tear it up,” he says. “They played so dynamically, but like a steamroller. They’d just burn it down.”), but as a father figure handing off his daughter.

“Natalie being only 18 or 19 when she joined the band, I told Martie straight up, yeah, she’s a great singer, but she’s never been on the road. She doesn’t know the ropes at all,” he says. “But the one thing that was comforting to Tina and I was knowing that Emily and Martie were extremely strong women. It was going to take a lot to pull the wool over their eyes.”

“Natalie being only 18 or 19 when she joined the band, I told Martie straight up, yeah, she’s a great singer, but she’s never been on the road. She doesn’t know the ropes at all,” he says. “But the one thing that was comforting to Tina and I was knowing that Emily and Martie were extremely strong women. It was going to take a lot to pull the wool over their eyes.”

Lloyd Maines also played some steel guitar on the Court Yard Hounds’ debut album, and his admiration remains unabated.

“I have so much respect for those girls,” he says. “I respect them not only as great musicians, but as really great people. They’re just good, strong women.”

Back at the ranch, so to speak, one of the good, strong women was musing about what success would look like in the Court Yard Hounds’ universe.

“I’d like to be in the black,” Maguire says with a laugh, adding, “I’d just like to maintain the life that I have, playing music and being able to give my kids whatever is important to me as a parent. I want the band to be successful to a degree that enables that.”

When she asked her children what they wanted to do this summer, they said, “We want to go on the bus!” harkening back to the days when each of the Chicks had her own tour bus and the families travelled together on tour.

“I had to explain to them that the individual tour bus days are over,” she says.

Maybe for the moment. But the Court Yard Hounds have come into their own. And, more than most, Emily Robison and Martie Maguire know there are many more turns in the road that lies before them.